Botanical Links

These are some resources that I use frequently and that I find to be very useful tools. I also ask my podcast guests what resources they use often, those entries are here as well. If you spend time in these places, soon enough. you’ll be a botanist, too :)

A social network for biology nerds…

No, seriously, that’s the best way to describe this place. And the best way to get in to the naturalist community, I think. Basically, you make a short profile and start uploading pictures of biology stuff (plants, insects, birds, mammals, whatever). They have a freakishly clever AI that will try to help you identify the thing you photographed, and then other members of the community will chime in and add their opinions as well. Eventually, if enough people agree on the ID, your observation can be used in scientific research and publications, how cool is that?! As you get better at identifying things, you can help other people with their observations. Really, just try; next time you go for a walk, take a picture of one plant and put it up there… you’ll more than likely get hooked.

The keepers of names…

I am a little bit obsessed with using the “correct” (most accepted) scientific name when I talk about plants. There are a lot of reasons for this, but in brief: using names inconsistently leads to much confusion. Biology is already confusing enough without adding imprecise language to the mix. This website is basically the hub, the repository, the managed, archived online database of Canada’s biological collections (including herbaria, the places where pressed, dried plant specimens are housed). Names are very important to herbaria because, like a library, they have a system of organization that uses the specimen name to decide where to store it. Besides names, you can also find images of thousands of herbarium specimens here. If you can’t visit an herbarium in person, this is the next best thing

A Masterpiece of human achievement…

If a bit on the abstruse side. This work, which has involved over 800 authors, dedicated botanical scientists, and which has been a work in progress for longer than I have been alive. It is a place where you can find incredibly detailed information on the appearance, range, habitat, genetics, flowering time etc. in language that sometimes appears to be closer to Latin or Greek than it is to English. And there illustrations here, some of the very best. The craziest thing about all this is that it’s FREE (though if you end up using it a lot, please throw them some cash because they deserve it!)

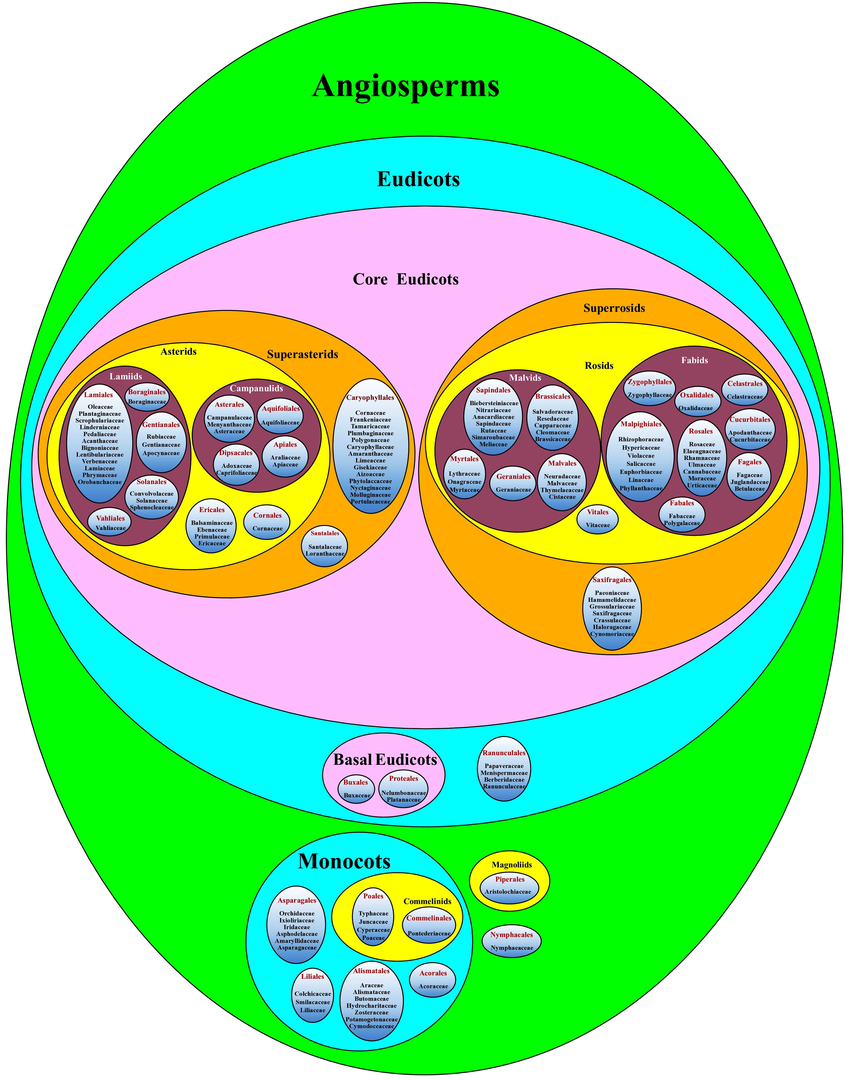

The keepers of the tree of plants…

Well, vascular plants anyway (we all have to draw the line somewhere). This is another pretty dense resource, but if you know how to navigate it, the information in here is an absolute goldmine for botanical research. It’s basically the entire evolutionary history of the kind of plants that have a vascular system: that’s all the flowering plants, the cone-bearing plants and the ferns (but excludes those fun squishy wet things like mosses, liverworts, green algae etc.). Again, it seems like this is written by aliens trying to speak English, but there is really no other place to find a detailed list of synapomorphies for a given vascular plant clade. And if those words don’t mean anything to you, don’t worry about it! (but probably skip this site)

The Flora I wish Ontario had…

But Ontario still doesn’t have a flora of its own. Luckily we have industrious neighbours. This resource is where I go most of the time when I want to identify an unknown or partially know plant. Getting all the way down to the species will be a bit of a slog, especially if you’re looking at a grass or a sedge, but you will be able to get there with some effort. Just note that Michigan does have some species that we don’t have (yet… cough climate change…) so it’s possible to take a short cut if you can rule out southern species. If I’m further east in the province I tend to use the next link instead.

The single best interactive key I have had the pleasure of using…

The New England Wild Flower Society really outdid themselves with this one. I’ve always been frustrated by dichotomous keys: they do get the job done but not very efficiently, especially if you have no idea what you’re looking at. The “Simple Key” feature on this site is a really cool tool where you can just start listing off things that you know about the plant (red flower, 5 petals, leaves 10 cm long etc etc. ) and it narrows down their database of species and photos until it’s usually manageable just to browse the results until you find a decent match. Works like a charm, for me anyway :)

How closely related is species A to species B, and what about….?

This is a really fascinating place where you can probe and query the evolutionary research and figure out how any species you are interested in are related (or, in other words, how recently do we think they had a common ancestor). For example, apples (Malus pumila) and oranges (Citrus x sinensis): pop them in to their tool and we learn…. about 106 million years ago, these species shares a common ancestor, meaning their evolutionary paths “split” somewhere around that time. What about strawberries (Fragaria) ? Are they closer to apples or oranges…? Where do Bananas fit in? Goof around here and you can learn a TON about evolutionary biology.

My favourite bunch of gardeners/stewards/activists…

In 2014, I was walking in Christie Pits park in Toronto when I noticed some green tents and a bustle of activity, and tables full of plants. Of course I needed to take a closer look, and to my amazement I found a group of people selling native plants (species that I usually only see when I go for nature walks) for people to plant in their gardens. Immediately, I knew I had to join them, and I’ve been with them ever since. Why? because balconies and community gardens and back yards can all be habitats, and they should be. Native plants have every right to be here, they are beautiful to look at, and tough and low maintenance. Planting them is the start of creating an functional, diverse ecosystem. Everyone can have that and the world needs a lot more of it.